Investor Education: Encouraging minority shareholder activism

Shareholder activism has been on the rise in Malaysia, especially in relation to issues such as directors’ pay and corporate governance. News reports have highlighted how some institutional investors, which tend to be substantial shareholders, have been making their voices heard by voting against certain resolutions at annual general meetings (AGMs).

In the light of this trend, the average retail investor — who is most likely a minority shareholder — should also do their part, say some industry observers, as this could affect the returns on their investments over the long term.

Shareholder activism can be loosely defined as any type of investor influence on a company’s decisions, including having a dialogue with the board of directors and voting against resolutions proposed by the company. In countries such as the US and Japan, activist funds acquire shares of undervalued companies and demand that management increase shareholder value.

In the past two years, two issues have made the headlines. In June, three institutional investors — the Federal Land Development Authority, Koperasi Permodalan Felda Malaysia Bhd and Lembaga Tabung Angkatan Tentera — voted against the proposed remuneration package for FGV Holdings Bhd’s board of directors, which took many observers by surprise.

In July last year, the Employees Provident Fund (EPF) strongly opposed the re-election of Sapura Energy Bhd’s directors, including its group CEO, due to the latter’s “excessive” annual take-home pay. During the AGM, shareholders also raised concerns about this matter.

“Retail shareholders should not be mere bystanders and leave all the work to the major shareholders, government-linked investment companies (GLICs) and institutional investors,” says Devanesan Evanson, CEO of Minority Shareholders Watch Group (MSWG).

“Retail shareholders are also owners of public-listed companies (PLCs). They should exercise their rights. There must be enough voices to hold the boards accountable. Bad directors make bad things happen in PLCs and because good shareholders stood by and did nothing.

“What we see [now] is more empowerment of GLICs to voice their opinions and vote as they deem fit when it comes to resolutions proposed by their investee companies. Such voting and articulation of thoughts by GLICs at general meetings are an example and motivation for minority shareholders to hold boards accountable for their actions and resolutions.”

But as minority shareholders, retail investors may find themselves voiceless if the majority shareholders vote differently. After all, institutional investors such as GLICs have substantial shareholdings in the country’s top PLCs by market capitalisation, according to reports. In this case, should minority shareholders still care?

“Yes, they should because the moment they invest in a company, they are buying a business. Although their portion is very small compared with those of the big investors, they may have invested 50% of their personal funds in that one company. So, retail investors must treat the company like their baby,” says Low Chern Hong, head of operations at 8VIC Malaysia Sdn Bhd, which conducts training on value investing.

“As retail investors, we have the right to attend AGMs. But forget about the free gifts. If you do not know enough about the company, just go there and learn from [the questions asked by] others. Attend a few more AGMs and you will know how to ask the right questions.”

He has observed from experience that many retail investors still eye the gifts and free food given during AGMs. Then, there are those who focus mainly on the share price and dividends without going deep into the fundamentals of the company. This is the difference between retail and institutional investors, he notes.

“Retail investors should not just observe the share price but also understand the fundamentals of the company, including its business model and [the capabilities of] the management team, which is something many institutional investors are concerned about. Many retail investors only look at the revenue and net profit. But they should also look at the return on equity, cash flow and whether the company has a lot of debt,” says Low.

While investors can glean this information from financial statements, they can also question the management directly at the AGM. Meeting the top management is an important part of valuing the company.

“We normally encourage our students to go to AGMs early and meet the top management. Based on my observations, the management of good-quality companies tend to shake hands with and meet shareholders before the AGM starts. When you talk to real people, you have a connection,” says Low.

It could be a bad sign if the top management do not take the shareholders seriously or fail to answer basic questions, he adds. “It is very important for the management to know exactly what they are doing because my money is parked with them.

“I have attended some AGMs where the board members did not really know how to answer questions. When we asked how they planned to increase their top-line growth and what their growth drivers were, they said they would increase prices and that they did not have any growth drivers but would give us dividends. That is not a good answer.”

Allen Yeong, managing partner at Vision Engage, which is involved in investor relations, has a similar view. Like Low, he has attended many general meetings and witnessed retail investors focusing on free gifts over the AGM process.

“Retail investors should have the goal of creating wealth. When they buy into a good company that can churn out more earnings every year, the share price will go up. That is why you want to buy into a company that can deliver results,” says Yeong.

The face-to-face time with top management is important because retail investors do not get special access to them, whereas major shareholders and analysts do, he adds.

How to make your voice heard

Yeong suggests that minority shareholders pick a “fight” they can win by researching how the substantial shareholders may vote. If they are likely to vote in a different way from the minority shareholder, the best thing one can do perhaps is to sell the stock.

“We should pick a fight where the ‘big boys’ will fight for us. The fact remains that due to the design of our financial system since 1997, our stock market is largely dominated by government and institutional funds as well as sophisticated investors. The upside to this is that our capital markets are [largely] insulated from shocks. But the downside is that retail investors can only ride the waves [when the large funds take action],” says Chua Zhu Lian, managing partner at Vision Group, which is involved in investments, advisory services and education.

On the other hand, a benefit from having a heavy presence of institutional investors in the top PLCs is that more often than not, what is good for them is also beneficial to the minority shareholders, says Devanesan.

But one factor that works against minority shareholders is that they may not know how the substantial shareholders will vote. These shareholders have different internal mandates and not all of them are made public. Their views on appropriate remuneration for directors could be subjective as well.

“Not all institutional and GLIC shareholders publish their mandates to allow minority shareholders to ascertain how they are going to vote. So, rather than being followers, the better approach for minority shareholders is to vote according to their conscience, regardless of how the bigger shareholders vote,” says Devanesan.

Regardless, steps have been taken to unite institutional investors. “The Institutional Investors Council (IIC) attempts to discuss issues on corporate governance collectively so they will be able to vote in a united way. The challenge is that not all the institutional investors are members of the IIC and their internal mandates may override the IIC’s stance,” says Devanesan.

According to its website, IIC members include EPF, Khazanah Nasional Bhd, Kumpulan Wang Persaraan (Diperbadankan) (KWAP), Lembaga Tabung Haji and Permodalan Nasional Bhd. Some of these organisations explain how they apply the Malaysian Code for Institutional Investors (MCII) in their compliance statements, which are published on the IIC website.

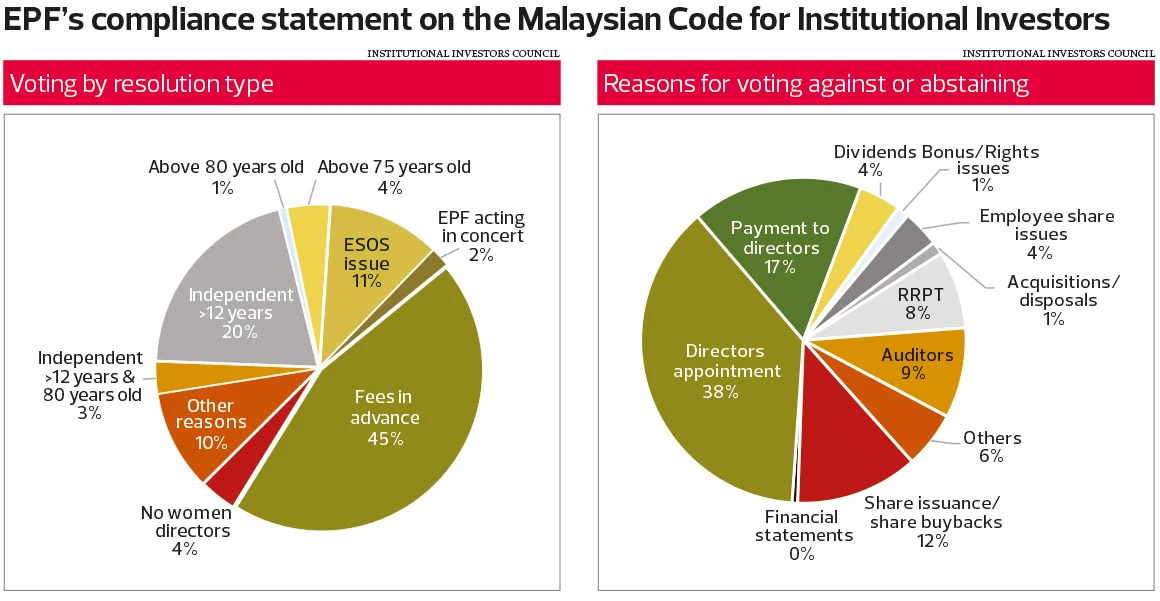

One of the MCII principles requires institutional investors to publish their voting policy on their websites. EPF, for instance, has a detailed report that gives examples of how and why it engaged certain companies on issues such as directors’ appointments, employee share issues and payments to directors.

Nevertheless, there have been times when majority shareholders or institutional investors vote in a consistent pattern. Devanesan cites Telekom Malaysia Bhd’s AGM this year as an example. Several institutional investors voted against the re-election of Gee Siew Yoong as a director, who also sits on the board of Tenaga Nasional Bhd. It was seen as a conflict of interest as both companies were involved in the National Fiberisation and Connectivity Plan.

Some institutional investors do publish their internal mandates on their websites. For instance, EPF’s voting policy states that it will vote against any directors’ reappointment if the company does not have any female directors on the board, according to a document posted online.

KWAP’s voting guidelines, which were posted in 2014, states that it will vote against the re-election of a director who has failed to attend at least 75% of the scheduled board and other committee meetings. It will also vote against the re-election of an independent, non-executive director who has served on the board for a cumulative term of more than 12 years.

Still, more needs to be done.

“Though the institutions and IIC have engagements with PLCs to voice their displeasure, very often it is not articulated at general meetings and other shareholders are not aware of this displeasure or the reasons for it. Other shareholders may read that an institutional shareholder has divested its stakes substantially without knowing the reasons,” says Devanesan.

“For shareholder activism to flourish, institutional investors must give their reasons for voting against a resolution and share their concerns when it comes to corporate governance issues, either before or after their material divestment.”

What should investors look out for at AGMs?

Remuneration is one of the corporate governance issues that are often brought up during AGMs. In Devanesan’s view, a shareholder can judge if the remuneration package is fair by comparing it with those of other companies in that industry.

“Shareholders do not have to do that work themselves. A responsible board would have done such a study and presented it at the AGM to justify the remuneration of the CEO. If a PLC does not do such a study, the shareholders should insist on it being done. It can be done quite easily as directors’ remuneration is a disclosure item for PLCs,” he says.

Since last year, all PLCs have had to issue a standalone corporate governance report using a template prescribed by Bursa Malaysia. Shareholders can go through this report and the Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance or the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s corporate governance principles to ascertain whether the company abides by the standards, says Devanesan.

For value investors like Low, directors’ remuneration is an important topic. If the company pays its directors a huge amount in remuneration despite weak results, it will affect shareholders’ returns.

He judges this by combining the total remuneration of executive and non-executive directors and dividing that by the company’s profit after tax and multiplying it by 100. “If the answer is more than 10%, we consider it to be high remuneration. The normal range should be below 10% for medium and large-cap companies,” he says.

Low also does not like companies whose directors have high fixed salaries. “Some companies give directors bonuses regardless of whether they perform or not. I like it to be based on performance,” he says.

“Let’s say a director is paid a fixed income of RM100,000. If the company records higher net income, then the director will get a higher bonus. The best thing is if the directors own the majority stake [in the company], so they are paid dividends as well. In this case, the interests of shareholders and the board of directors are totally aligned.”

Chua and Yeong have similar views on this. “Normally, companies with better corporate governance tend to be heavier in their dividend payouts compared with the management’s remuneration. That is a simple rule of thumb to see what the management team’s dominant mentality is. Do they want to reward all the shareholders or just themselves?” says Chua.

Other common corporate governance issues retail investors should look out for are the long tenures of independent directors, especially those who have served more than 12 years without two-tier voting, and if the executive chairman is also CEO, which could give an individual too much power. The granting of employee stock options or share grants to independent directors, the election of directors who sit on other PLCs with competing business interests and a lack of boardroom diversity are worth looking at as well, according to Devanesan.

Low encourages investors to interact with the top management at AGMs and ask them questions that cannot be addressed in reports. He also likes to gauge the integrity and sincerity of the management team.

“At the AGM, the first question is not to ask about their performance but whether they made any mistakes last year. It is a classic question that we teach our students. It is not to embarrass the management, but to let them admit they made mistakes. The biggest mistake a human being can make is to never make mistakes, so we believe the management must have integrity [to admit that],” says Low.

Right after the AGM ends, do not make a beeline for the free food, he adds. “You must go and shake hands with the board of directors. Ask the directors questions that they may not have been able to answer during the AGM but can do so personally.”

The emphasis on sincerity is something Yeong also identifies with. Prior to attending an AGM, he analyses the financial performance of the company. “I can accept if the company underperformed for one or two years. But if the performance has been consistently weak and management has been using the same story to explain the underperformance again and again, I will probably not stay invested in the company,” he says.

Additional resources for retail investors

There are many things retail investors can learn from annual general meetings (AGMs). For instance, Low Chern Hong, head of operations at 8VIC Malaysia Sdn Bhd, has learnt much from the representatives of the Minority Shareholders Watch Group (MSWG), who ask tough questions at AGMs.

“As a retail investor, I have learnt a lot from them. They also have weekly articles that point out what questions investors can ask particular companies about their corporate governance practices. This is a very good resource,” he says.

MSWG has a weekly newsletter with analysis on selected companies and questions that investors can ask at upcoming AGMs.

Retail investors can get a free subscription to its weekly newsletter, gain priority booking for its Investor Education Programmes (IEP) and access its monitoring services such as its letters to public-listed companies (PLCs) and their responses to its questions. The IEPs include forums that MSWG holds before some AGMs and various topics of interest to shareholders such as merger issues and special dialogues on the Asean Corporate Governance Scorecard.

But it is not just about asking questions at AGMs. It is also about building relationships, says Low. “It is not only to challenge the companies but also to make friends with them. Retail investors should also have a good relationship with the investor relations team of the company because you may have a chance to visit them one day.”

MSWG CEO Devanesan Evanson says the organisation is in the midst of reinventing itself to be more effective and efficient. For instance, it is exploring the possibility of providing training to boards of directors, senior management and the general public on corporate governance.

MSWG already has corporate subscriber packages, where it offers each PLC a report card on their corporate governance performance, among others. It is used bi-annually for the assessment of PLCs in Asean.

“With the scorecard, PLCs can ascertain where they rank compared with other PLCs. We can also have training sessions for boards and PLCs on the expectations of minority shareholders,” says Devanesan.